Vietnamese language (tiếng Việt)

When commencing to learn Vietnamese you have a very happy start at first and even at second glance!

At first glance you will realise that Vietnamese is the only Asian language that uses Latin letters with some accent like funny bows, lines and dots that don’t seem to bother you much (remember, we’re still at first glance!). In the 17th century some Portuguese missionary had put a hell lot of effort into “translating” the Vietnamese language (then a similar sign language like Chinese) into Latin letters. They used the above mentioned bows, lines and dots to address the pronunciation of the vocals and words. This sounds pretty easy, so no worries..

At second glance, you will realise that the grammar is incredibly easy: no conjugation, no declination, no past tense, no past perfect, no future, no subjunctive, no active/passive voice – heaven !!! (foreigners who have tried to learn German or French will know what I mean). Guess, now you think “how can this work?”. Quite easy: if you want to talk about something that already happened in the past, you just have to add the word “đã” in front of the present-tense verb (it means something like “did happen”) and you’re done. For example, “đã nấu cơm” means dinner already cooked, “đã thấy” means already saw/seen. Couldn’t be easier, right? Same is true for the future tense with adding “sẽ” (will happen).

The first and biggest real hurdle though is knowing the right personal pronouns to use. In Vietnam, family and hierarchy within the family plays a major role in the society, which is also reflected in the language. The most respectable persons in the family are the (great) grandparents (ông – grandfather, bà – grandmother). You use these personal pronouns when you talk to them or to someone clearly older than you that you want to show your respect to. For uncles and aunts there are different pronouns depending on whether they belong to your mother’s or your father’s family – and there are usually many of them on both sides. To make things easier, the Vietnamese have a habit of calling their child by the order they’re bornt, but starting with No. 2 (don’t ask me why..). So for you as a child, “cậu tám” (uncle eighth) is the seventh child of your mother’s family (not the seventh son because there might be “dì bảy”, aunt seventh, before him). Correspondingly, “chú” and “cô” are uncle and aunt from your father side. Even when addressing yourself, you have to use different personal pronouns depending on whom you are talking to. For example, when I talk to P, I call her “em” and address myself as “anh”. But “anh” also means brother and “em” a younger sibling (could be either boy or girl). So if you, like me, used the same pronouns while talking to my future mother-in-law, she’d burst out laughing because from her perspective, you are “con” (child, children), and only her husband or her older brother are allowed to call her “em”. See where i’m getting at?

Once you start to recover from all these confusions with the personal pronounces, you will realise the real challenge is still in front of you: the pronunciation!

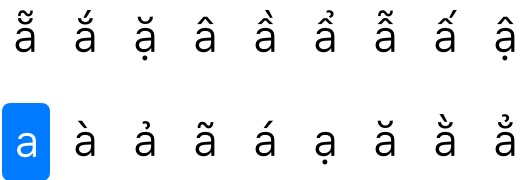

I briefly mentioned some bows, dots and lines above: they either tell you how to pronounce a letter or how to raise or lower your voice when saying a word. There are six “tones” in the Vietnamese language but I will only mention two as an example: “tám” means “eight” and the little accent on top of the “á” means that you have to raise your voice just like you continuously raise a tone in a piece of music. You already know the word “bà”, the accent here telling you to lower your voice. And here the trouble starts! Vietnamese is a one-syllable language, i.e. each word consists of one syllable only. Hence the variety of different words is much more restricted compared to languages with multi-syllable words (and yes, Germans have certainly optimised the art of creating unending words!). Even foreign words adopted from other languages have been split into one-syllable words as well: e.g. the French word “café” became “cà phê” in Vietnamese. By using the accent the Vietnamese try to mimic the pronunciation of the original language, adopted to their own. That way though, the same set of letters can have multiple (!) meanings, just by adding different bows/dots/lines. There is certainly not enough space here to go into more details, the combinations of the letter “a” below will give you an idea of how many different pronunciations there can be:

And each one of them has to be pronounced differently as well (!). Doing it wrong can give a word an entire different meaning. Take the word “ba” for instance. It means “father” (remember, it is also the personal pronoun for your father-in-law) and “three” at the same time. Now imagine you use the word “bà” instead (same as “ba” but lowering your voice as you speak). You either call your father-in-law grandma (which may cause laughter when you’re lucky) or you may order a “grandmother-beer” instead of “three beers” – whatever a granny-beer may be ;-). In another example you may order “cơm gà” (chicken rice) in a restaurant , a dish the beautiful city of Hội An is very famous for, or you could as well order “cơm ga” (forgetting to lower your voice when saying “gà”) and the waiter would just ask himself what you mean by ordering “railway station rice”. Therefore, using/saying the wrong accent will very likely make you misunderstood. Finally, imagine a native talking to you at THEIR normal speed using all those short words that sound so similar to your European ears.. Now you’ve got the whole picture.

Nevertheless, this short article isn’t to say Vietnamese language is impossible to learn. Many people have done it and you can do it as well. I personally have met a German guy in Munich that could speak Vietnamese so fluently that even P was totally amazed. The pronunciation is difficult yes, but it’s also fun and the (very friendly) people in Vietnam will appreciate it very much if you try!

Chào tạm biệt (see you)